Blancpain

A History of the Dive Watch

Blancpain

A History of the Dive Watch

In the past, buffering a watch against the entry of dust and water usually meant using beeswax to seal the snapback cases ubiquitous on the pocket and early wristwatches. Still, it was a habitual ritual for a man washing his hands to remove his watch and set it safely to one side before doing so and rare is the vintage snapback watch without at least a few specks here and there of corrosion on the steelwork.

Enhanced Water Resistance

In 1926, water resistance in timepieces took a leap forward when Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf patented the Oyster case, featuring screwed-down crown and caseback which are as ubiquitous among dive watches today as the name Rolex is recognizable around the world.

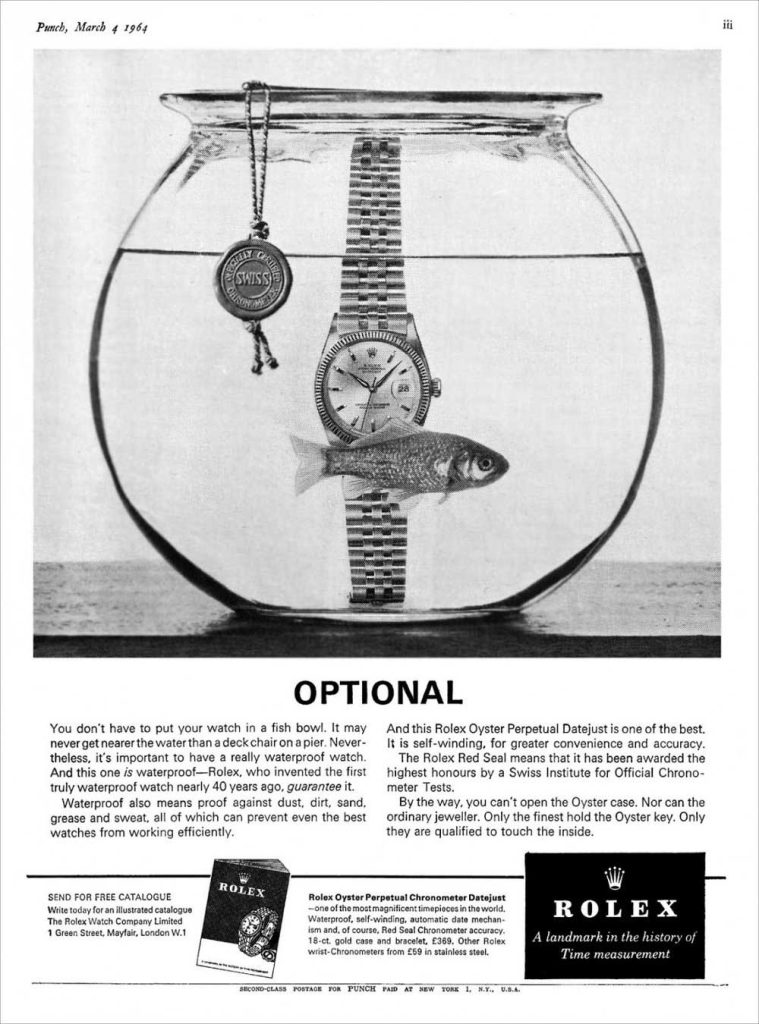

Magazine ad extolling the waterproof capability of the Oyster case

The often repeated story that Cartier’s first water-resistant watch was the “Pasha”, and that the Pasha was inspired by the Pasha of Marrakesh’s request for a water-resistant watch to use while swimming, is just that — a story. At the time (the mid-1930s), according to brand historian Franco Cologni, the Tank “Étanche” was the only water-resistant watch in the Cartier stable — the Pasha didn’t debut until 1943.

The Tank a Vis, a 2001 re-edition of the very rare Tank Etanchée (© George Cramer)

First Dive Watches

The leap from a water-resistant watch, which would defy splashes, to a dive watch, can probably be credited to a firm whose name was intended to literally imply the last word in precision — Omega. In 1932, Omega came out with the Omega Marine. The Marine, it might be argued, is not a purpose-built dive watch in the modern sense either, with no rotating timing bezel, no screw-down crown and caseback. But it solved the issue of water resistance in a way that no other watch before had managed to do. It had a rectangular case that slid into an outer case, with a lever that created a hermetic seal between the two. The Marine also had a sapphire crystal, one of the first watches to do so. And it was tested to depths no watch had ever been taken to before — 73 meters in Lake Geneva, and then in a pressure chamber at a laboratory in Neuchâtel to a pressure corresponding to 135 meters depth.

Omega Marine (Image: auction.catawiki.com)

Marine 1932, Omega’s re-issue of the Marine watch in a 135-piece limited edition in 2007

Marine 1932, Omega’s re-issue of the Marine watch in a 135-piece limited edition in 2007

Marine 1932, Omega’s re-issue of the Marine watch in a 135-piece limited edition in 2007

Hamilton USN BuShips (US Navy Bureau of Ships) “Canteen” watch (Image: liveauctioneers.com)

Panerai Radiomir, circa 1942. (Image: Christie’s)

Postwar Era: Rolex Submariner and Blancpain “Fifty Fathoms”

In the postwar era, scuba diving gradually became more and more popular both in industry and with the general public. The competition to go deep produced the deepest diving vessel ever to carry a human crew, the bathyscaphe Trieste. The Trieste was more akin to a hot air balloon than a conventional submarine. Basically, it was a spherical pressure hull — a bathysphere — suspended below a huge gasoline-filled float which gave it buoyancy. It took humans deeper than any submersible before, or since, had done — all the way to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, one of the deepest spots in the ocean, at over 10,000 meters deep.

The bathyscaphe Trieste in dry dock

The Rolex Deep Sea that descended beyond 10,000m in 1960. (Image: Rolex)

Rolex Submariner Ref. 6205, circa 1954 (Image: Christie’s)

Blancpain Fifty Fathoms, circa 1953

Blancpain Fifty Fathoms Automatique in red gold

Panerai dive watch with Luminor crown guard made for the Egyptian navy, 1956 (Image: Christie’s)

The People’s Ocean — the Modern Dive Watch Era

The diver’s watch took on the classic shape we know today in the 1950s, and in the ’60s the undersea world became everyone’s world. Diving went from being a sport practised by a few hardy souls — many of whom were building their own regulators out of spare valve parts meant for other industrial uses — to a sport that, as equipment got cheaper, thousands and then millions of people around the world enjoyed.

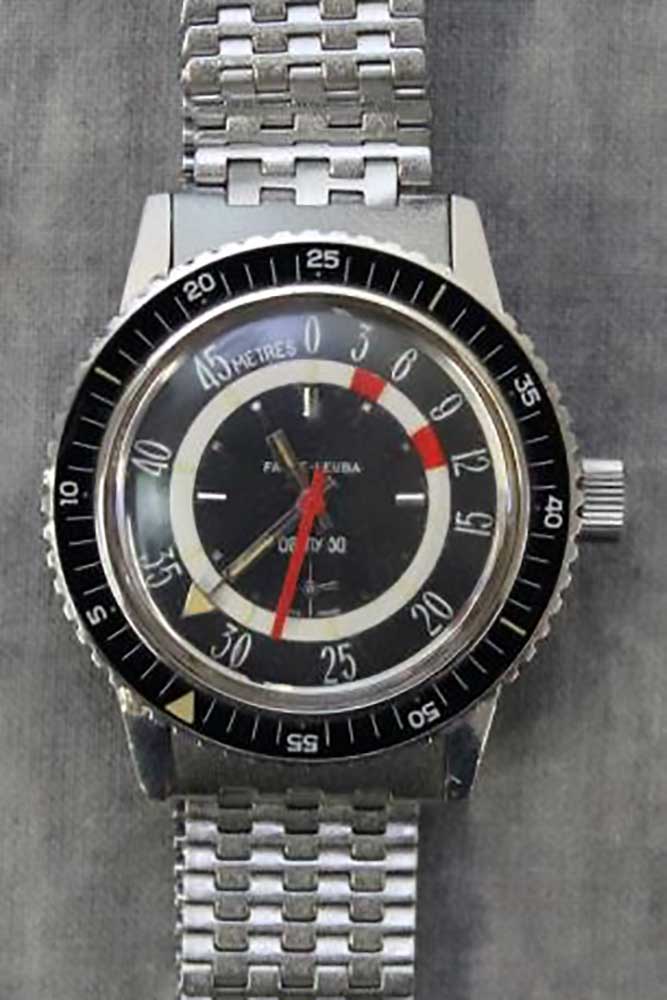

The sheer variety and number of dive watches began to boom — Tudor, Enicar, Eterna (with the classic Kon-Tiki model), Eberhard and many others fielded watches intended for divers and, increasingly, also for those who wanted something bold, tough and bulletproof on their wrist to announce their endorsement of high-risk, tough-guy values. Favre-Leuba developed a real milestone, however — the famous and now nearly impossible to find “Bathy 50”, the first dive watch with a functional mechanical depth gauge, also sold as the “Bathy 160” with a dial calibrated in feet rather than meters, first sold in 1966. And yet another milestone was reached by a company whose name has likewise been largely forgotten outside the group of genuine dive watch history fanatics — the Jenny Caribbean was the first diver’s watch to be rated to the magic number of 1,000 meters.

Favre-Leuba Bathy 50. (Image: liveauctioneers.com)

Saturation divers typically work in a heliox rather than a nitrox atmosphere, which can create problems for a dive watch as the helium atoms are small enough to actually penetrate the seals and gaskets of a dive watch, and build up inside the case. The problem was, during decompression, the built up pressure could shatter crystals, or pop them off the watch entirely. The solution to this was the second iconic Rolex diver’s watch, the Sea-Dweller, which was launched in 1971.

Rolex Submariner featuring the helium escape valve developed with COMEX for saturation diving

The list of technical Seamaster watches is a long one, but the big kahuna of the lot was and remains the Seamaster 1000, which outsizes and can outdive even Omega’s other big contender in the dive watch derby, the asymmetrically shaped “PloProf” 600 meter watch, with its signature bright orange button for locking the dive bezel. The Seamaster 1000 is another one of the extremely small club of diver’s watches to have been worn by a submarine as well as by human divers — in 1973, the American firm International Underwater Contractors strapped an Omega Seamaster 1000 to a manipulator arm on their Beaver Mark IV deep sea submersible, and took it to a real-world test depth of 1,000 meters. Multiple tests confirmed the performance of the Seamaster 1000, which looked back out at the undersea world through its 5-mm-thick crystal with imperturbable aplomb.

Omega Seamaster 600 Ploprof

Seiko also had a high-tech, high-mech first in 1975, with the world’s first titanium production watch, the Seiko 600 meter Pro Diver, with a gasket system sophisticated enough to prevent helium from entering the watch in the first place — their massive (51mm) answer to the other purpose-built saturation diving watches, the Omega Seamaster 600 and 1000, as well as the Rolex Sea-Dweller.

Seiko Ref. 6159-7010, the company’s first watch designed for saturation diving, introduced in 1975

Modern watches that take water and corrosion resistance to new heights and depths, like the submarine steel-crafted Sinn U1, or its contrastingly light and lively counterpart, the titanium (and 3,000-meter water-resistant) Breitling Aeromarine Avenger Seawolf, continue to give divers that extra edge they need in the delicate chess game of gases and pressures that ensures survival in the deep. And increasingly, it’s a game that has advanced beyond the fundamentals of staying alive to yield a golden harvest of diver’s tourbillons, minute repeaters, and other complications protected by sophisticated case and gasket systems that would do a physicist proud.