Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre Factory Visit: Where the Heart is

Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre Factory Visit: Where the Heart is

Master Grande Tradition Gyrotourbillon Westminster Pérpetuel

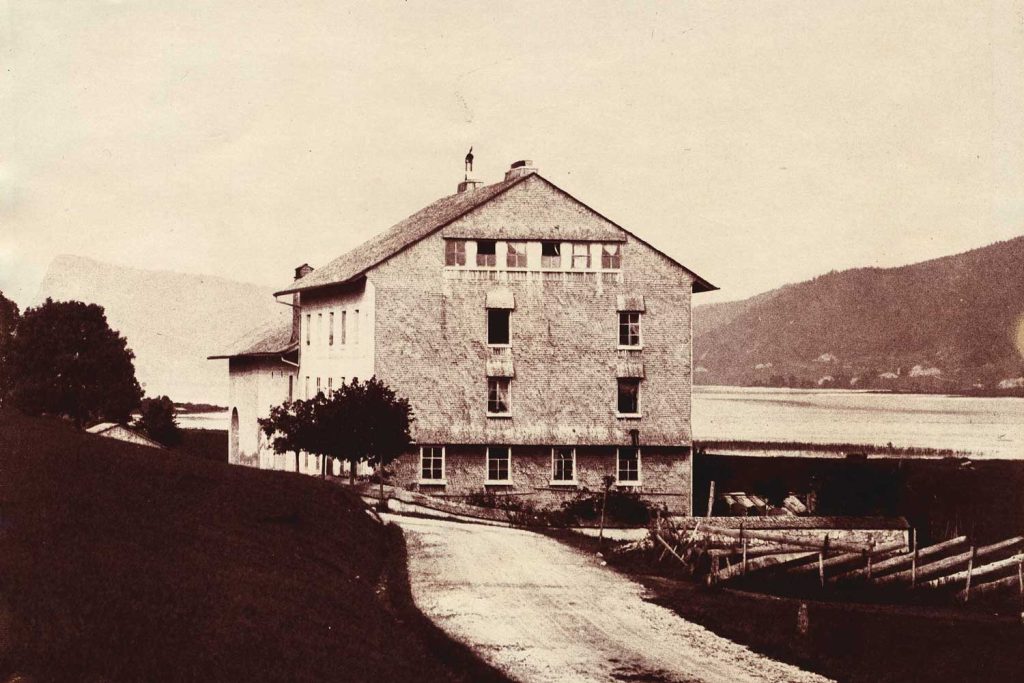

For more than a century, Jaeger-LeCoultre has been considered one of the pioneers in the watchmaking industry with notable innovations. Today, standing in Le Sentier with 25,000 square metres of space, the manufacture houses more than 1,200 staff. They were the first in the Vallée de Joux to incorporate all departments in the same building under the management of father and son, Antoine and Elie LeCoultre, and it was on these grounds where more than 1,200 in-house movements were developed.

Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture, Le Sentier, present day

The restoration workshop works to rebuild vintage movement parts and fully restore old timepieces

The original manufacture

Offering up his greatest hits, Laurent immediately began presenting Jaeger-LeCoultre’s finest high complications to us, including past Gyrotourbillons that led up to this year’s piece. “What we do here is try to evolve every single generation of Gyrotourbillon to improve precision,” says Laurent. “Sometimes even starting from zero and recreating totally something new rather than improving the tiny details.” Among them was the 2015 version of the Master Grande Tradition Grande Complication, that began with the first iteration in 2010 which formed the Master Grand Tradition line. Dominated by a blue sky chart dial speckled with constellations and a month indicator, an orbital flying tourbillon flies daintily overhead. From the case back, one can watch the hammers striking the crystal cathedral gongs of the Westminster Chime minute repeater complication.

Jaeger-LeCoultre watchmaker Christian Laurent

Engraving a movement component

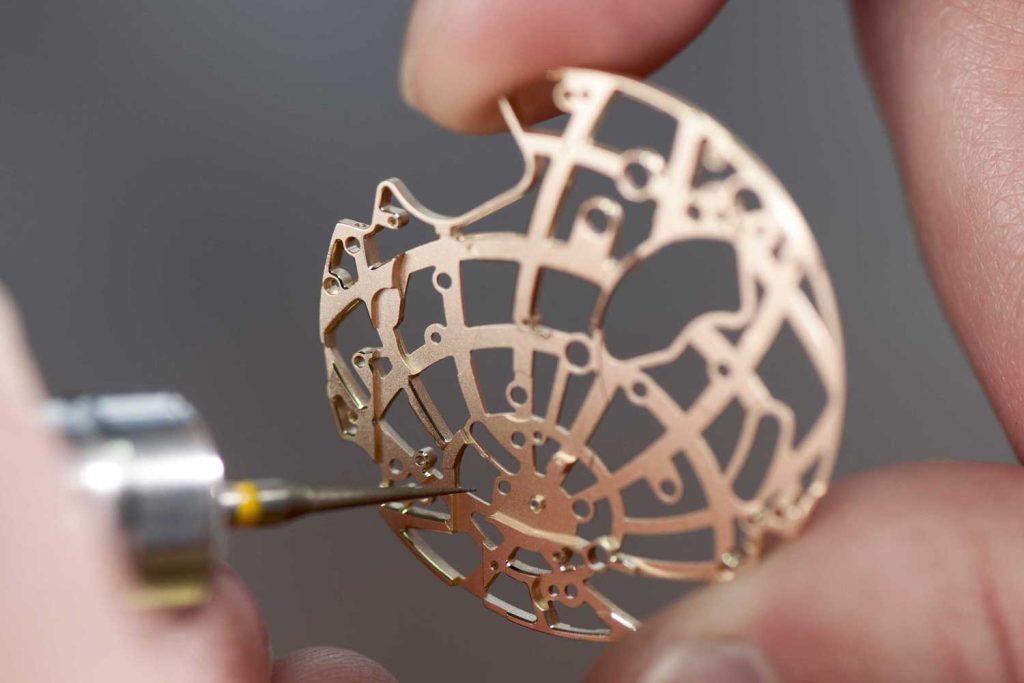

Skeletonising a movement

Heritage Gallery within the manufacture featuring a wall of calibers

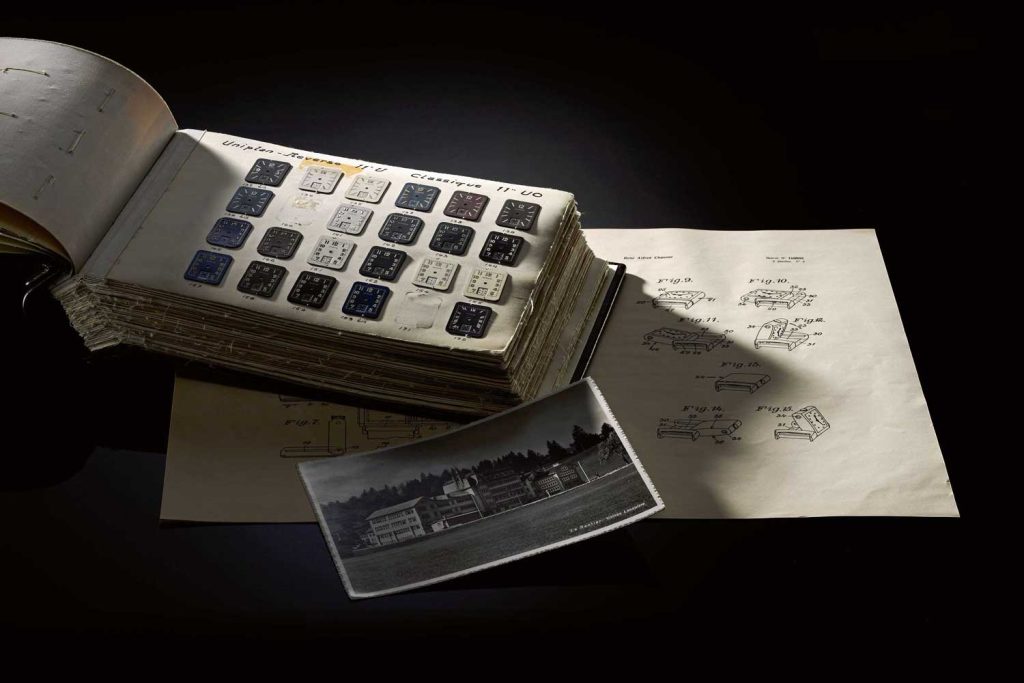

The Heritage Gallery houses all the archival material of the maison

Dial designs and an archival document for the patent of the Reverso case