News

Reliving History with James Ragan: NASA’s Man Behind the Moonwatch

News

Reliving History with James Ragan: NASA’s Man Behind the Moonwatch

“They called me in and said, ‘We need a watch.’ And I said, ‘I thought you hired me for photographic hardware.'” But Ragan tackled it anyway (it was a job at NASA no one was going to give up on that easily). To figure out what the astronauts needed the watch for, Ragan spoke extensively with the two Gemini crews. In the end, he concluded that what the astronauts really needed was a chronograph, since they relied on the timing function as a backup in case they ever lost communication with mission control.

Mission control

Slayton might have issued the letter, but it was Ragan who engineered the tests. He was responsible for putting the watches under trial, for proving that the watches were fit for space travel. Of the brands contacted, only four responded and Ragan purchased three of the listed chronographs for testing. The only watch that made it through the series of stringent tests was the Omega Speedmaster. Since then and to this day, it is the only timepiece NASA has certified and allowed its astronauts to wear to the moon.

Petros Protopapas and James Ragan chat about the latter’s NASA experiences during a recent visit to Hong Kong

Ragan’s been telling his story since the 60s, but still, little details in the moon landing epic still surprise us. We’ve picked out ten anecdotes, told by Ragan himself. Like they say, history is best when told by the people who lived it.

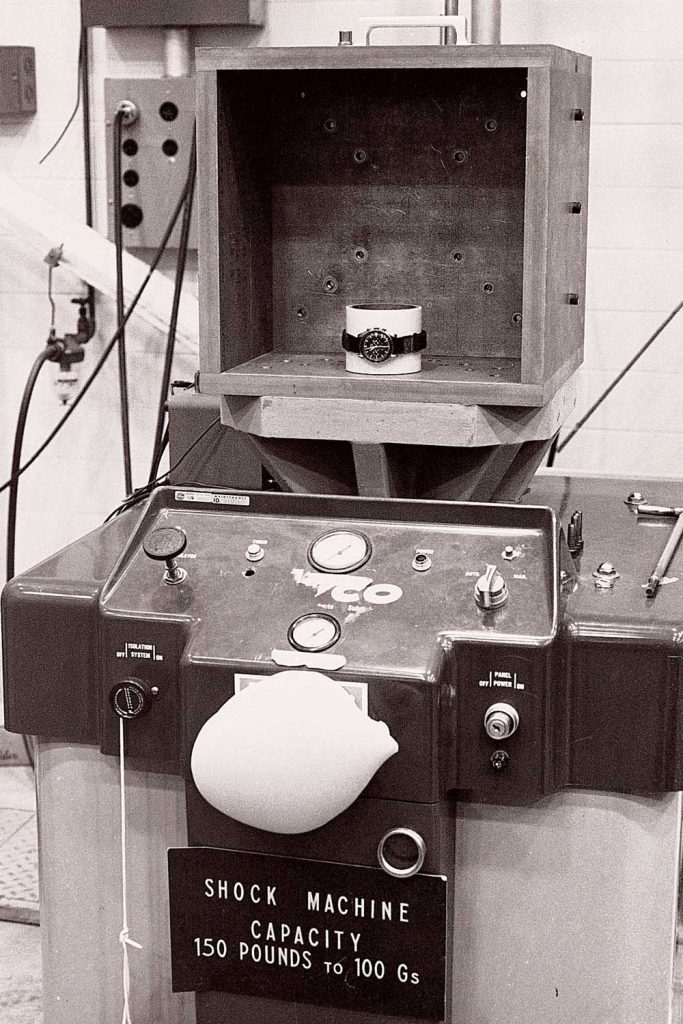

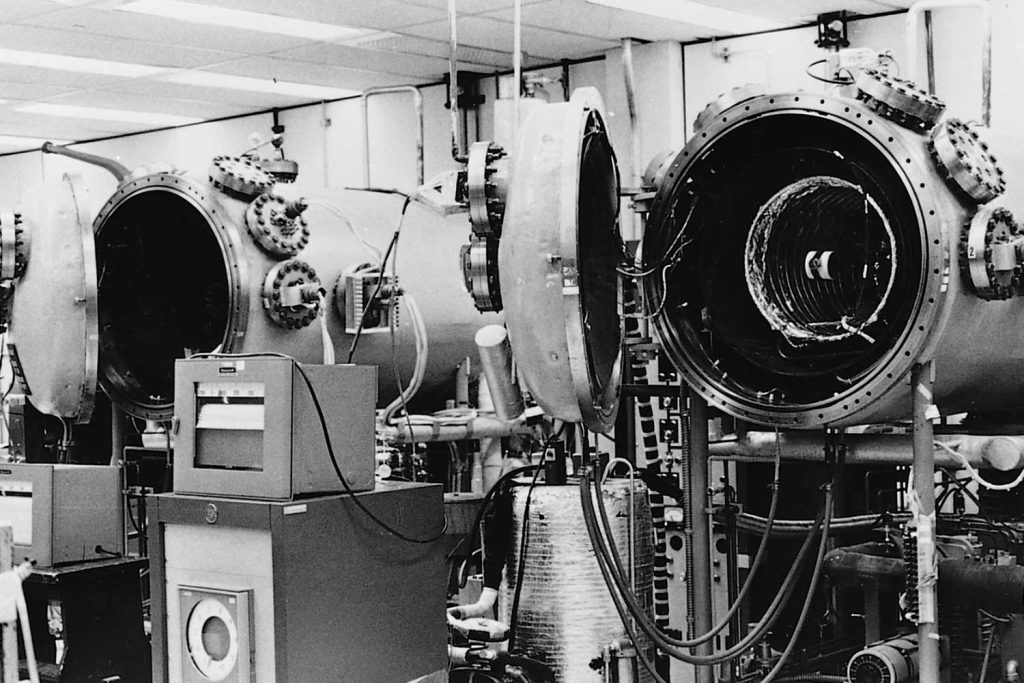

1. The ten-step trial that the watches had to go through to qualify for space flight is really intense, even Ragan thought so.

“In a typical government today, in the US, I can’t just go buy Omega or Bulova, whatever chronographs we got out there. I had to write a specification. And here’s what I want: it has to be off the shelf because I didn’t want to develop anything. We had to put out this specification and also had to give them what environments they had to pass. Safety, reliability, quality, define what you had to do to qualify a watch, or any piece of hardware to be used.

When I saw the requirements, I went back to them and said, ‘Hey, you know, this doesn’t make a whole lot of sense because I’m going to have a watch strapped on an astronaut. And you’ve got a requirement that I’m going to bolt a piece of equipment here and see all the shaking and rattling of the vehicle. The body dampens out a lot of that.’ Well, I didn’t win that fight.

Putting the watches through a series of stringent tests...

...in order to certify that they were qualified for space flight

Of all the environments that they made me do, the one that stood out the worst was the thermal vacuum test. You pull the watch down to a hard vacuum. And then we put a heater around it, I had to test the watches at 0°F to 160°F. That’s tough on anything, let alone a watch. The Longines and the Rolex failed on the first test.”

The watches are exposed to extreme temperatures on the first test

2. The ten brands that received the NASA request were selected almost arbitrarily, but anyone could have sent in a watch for testing.

“I had to come up with [the list]. I could add that my requirement was to get ten brands and they could go out. And this was all published. And not only we sent them out for those ten brands, I asked them if they would want to put in a proposal, same cost and all that. But anybody that made watches back then, if they wish, they could get a copy of that. It was not limited to those at all. But it was easy because you know, they had it in all the department stores. Whether they made a chronograph or not I doubt it, but at least I had the ten names.”

3. Only three of the four watches submitted were tested because one of them was not a wristwatch.

“Only three were tested because the first one was made to be mounted on a ship. It was a chronograph but it was so big and we specified that it had to be a wristwatch, so immediately that was easy to get rid of. I didn’t have to do anything.“

4. We now know that the watches that failed the testing procedure all failed quite early on.

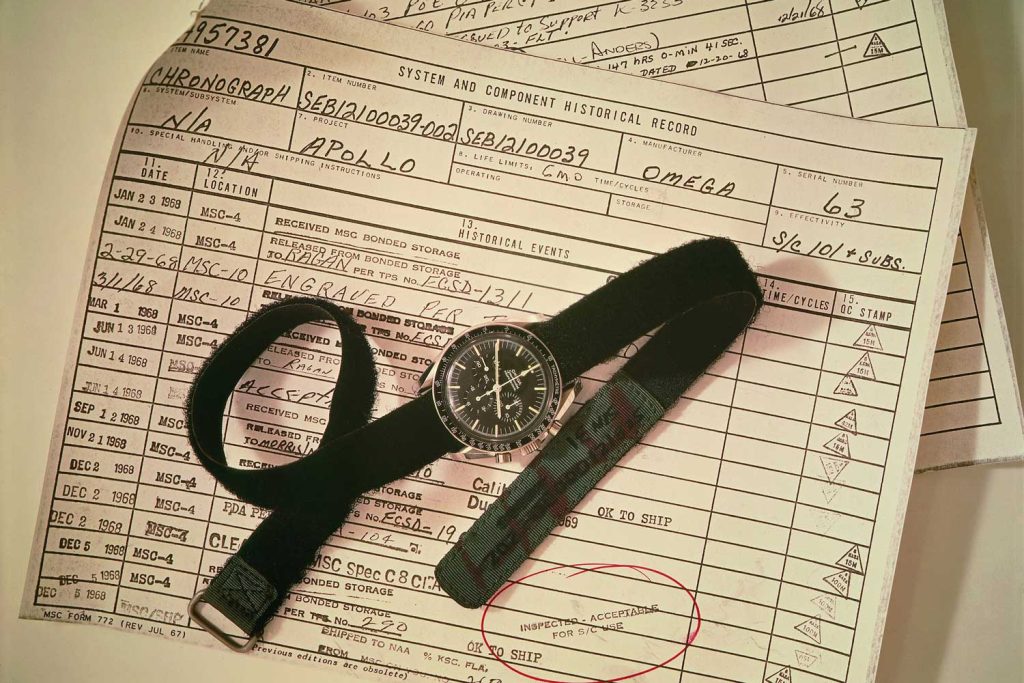

“Once we had a failure and could not get it to work any longer, then that was through. So the first test, I got rid of all but one. And now, I was worried about not knowing whether this one was going to pass or not too. I wasn’t sure if we’d ever find one that did all of that, I figured out a waiver of some kind, but Omega made it through with flying colours. And then, I went back to the astronauts and said, ‘Okay, please tell me what’s your evaluation of the three that I gave you.’ And everyone preferred the Omega, they were easier to use. The astronauts liked it and it made my job a lot easier. So I sent all those requirements back to safety, reliability and quality, people who certified the things with all the inspections and the stamps saying we passed the test. It was three weeks before we got it, we got a piece of paper saying this watch is certified to fly.”

Everything the Omega Speedmaster went through is recorded thoroughly in NASA’s system

5. Until recently, we thought the astronauts only wore one watch to space, but some of them wear two: the one they get on the mission and their training watch.

“It was instrumental for the astronauts to get these watches early in their training. So at least six months before any mission, every astronaut that was flying with the range of time — I didn’t have a lot of watches to give all of them — we gave the two or three missions coming up with training watches, so they could use them in the simulators and when they flew with any aircraft and did all of the experiments that they did. The ones I wanted to fly on the mission, and the suit tech who put it on strap the watch on their arm just before they went out on the pad.”

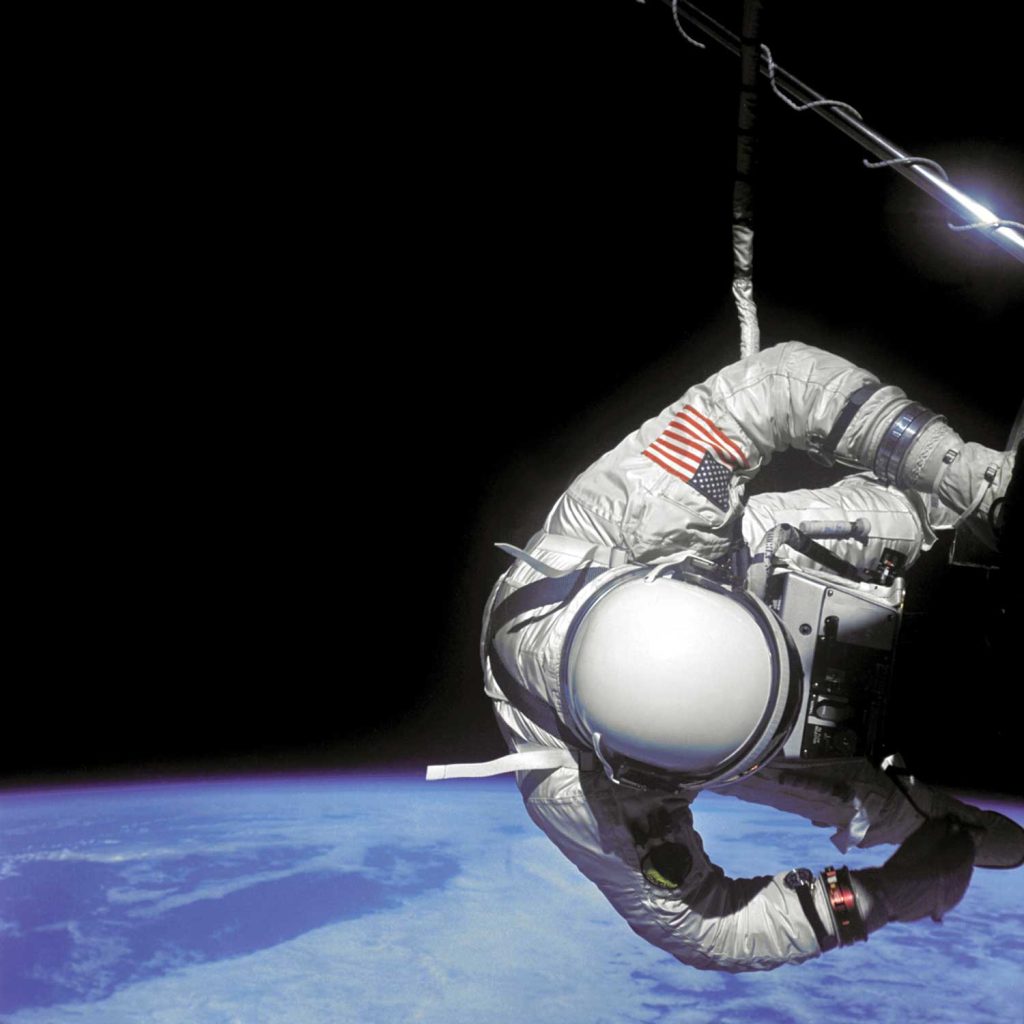

Two watches are clearly seen strapped to the arms of the astronaut

6. Some astronauts treated the watches like they were their lucky charms.

“Most astronauts, once I assigned them their first watch, they kept in their head what serial number it was and so I would have astronauts that if they flew with it once, they’d want to fly with it again. The two most famous ones were serial numbers 27 and 28. They first flew those on the Gemini days. Our good friends Thomas Stafford and Eugene Cernan, it was their watches. Tom had on the 27 and the 28 was Eugene’s and they wanted to fly with them no matter what.”

7. The original Omega bracelets were too durable, and were not used by NASA in order to protect the astronauts’ arms from breaking if there was an accident.

“Watch collectors are going to know this but I was always concerned with these heavy bands on those watches because once these guys were in their suits and it’s blown up, they were like human bulls in a china shop. So I started looking around and found a JB Champion band. And I used that on every training watch. Those things would break right where the pins went in, if the astronauts got caught [on something] , you know? I broke off many of those things, 2,000 of those JB Champion bands. You can’t buy them anymore, they don’t exist anymore. But I never got an astronaut’s arm torn up.”

The watches are fitted with breakable Velcro straps to ensure it won’t trap an astronaut’s arm in case of any mishaps

8. Ragan only allowed one guy to service the moon watches, no one else.

“Once I knew who was going to be the distributor in the US, I called them and said, ‘I’d like to negotiate a maintenance contract with you because I don’t want anybody to know what Omega watches we’re working on.’ And they said fine, and we negotiated a price which was fair to me. And I said, ‘Okay, now I want to go back and interview your technicians who work on the watches.’ And they thought I was crazy. I said I’m not going to let just anybody work on the watches. I want to go interview. I went through everybody and I went through the whole gamut. I found one guy. I think until he died, he was the only one who was allowed to touch those watches. I get a complete report from them saying this is what they’ve done, this is what they found, this is what they replaced. And we put all those on every piece of hardware that NASA flew, a part number and a serial number.”

9. For space, mechanical watches trump digital watches.

“We had an astronaut or two that wanted a digital watch and so they would come to me and I said, ‘It’s never going to work, you’re not going to have one.’ If it was only on the inside you’re all right, but not outside. But why? I had to test for zero to 200 degrees Fahrenheit. At the time they had two watches, one was an LED watch which would bother the battery. And once you got it out in the sunlight, you couldn’t read the LED because the liquid got so hot it flowed so fast you couldn’t read it. It looked like there was nothing on there. And when it got so cold, it froze and you couldn’t read it either. So there’s no way of doing it unless we’re just going to keep it on the inside. The Omega X-33 Skywalker is only allowed to be used on the inside. The only watch today that’s qualified to go outside is the Omega chronograph.”

10. Omega is NASA’s longest single supplier since the Gemini days.

“I get approached by several different companies and my reply was that there is no reason for the government to go buy new watches when I’ve got watches that are perfectly capable. We own them and all it costs is service. I have no requirement to buy new watches. But it might be different today.”

The CK2998, the first Omega Speedmaster in space, was a personal watch belonging to Walter Schirra, and not tested by Ragan and NASA beforehand

The Ed White II Speedmaster Pre-Professional, the model worn by Ed White during his first EVA for NASA during the Gemini IV mission

The first “Moonwatch,” worn by the astronauts of Appollo 11

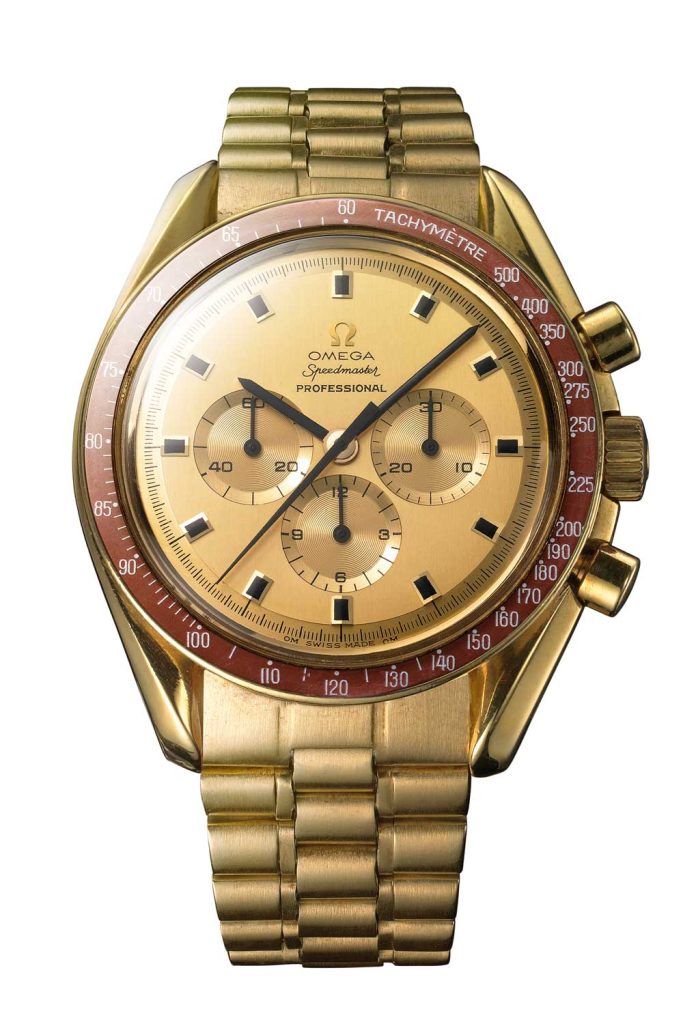

Gold models of the Speedmaster created in 1969 to commemorate the achievements of the Apollo 11 crew. This particular model is engraved for Spiro Agnew, then Vice-President of the United States