Patek Philippe

The Entire History of Patek Philippe’s Perpetual Calendars

A clever plot device of the leap year is employed in The Pirates of Penzance

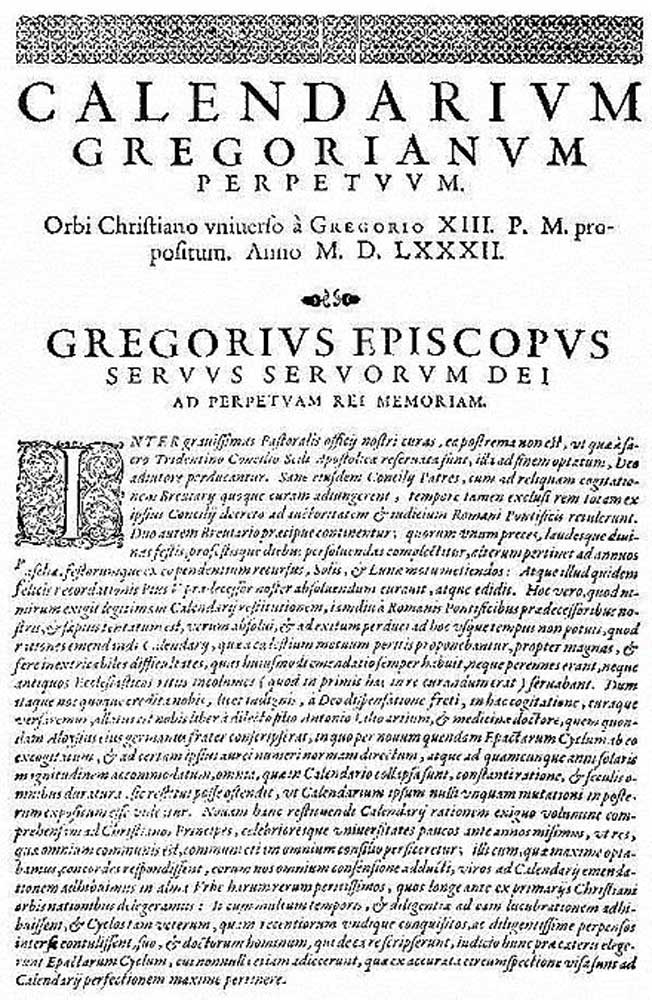

It turned out this was all down to a pope named Gregory XIII who in 1582 instituted the Gregorian calendar, which corrected faults in the Julian calendar. The issue essentially was this: the calendar year where time is divided into 24-hour days, seven days a week and 30 or 31 days a month with 28 days in February for a total of 365 days is actually shorter than the solar year, which is how long it takes the Earth to revolve around the Sun. This is actually 365 days, five hours, 49 minutes and 16 seconds to be precise. To compensate for this, Pope Gregory XIII added the day of February 29th once every four years. But this in turn creates a slight overage so that every 100 years, though divisible by four, the leap day is left out. Every 400 years, it is put back in. Still with me?

First page of the papal bill issued by Pope Gregory XIII that decreed the Gregorian calendar into existence

Earliest known perpetual calendar watch, created by Thomas Mudge in 1762. Image: Sotheby’s

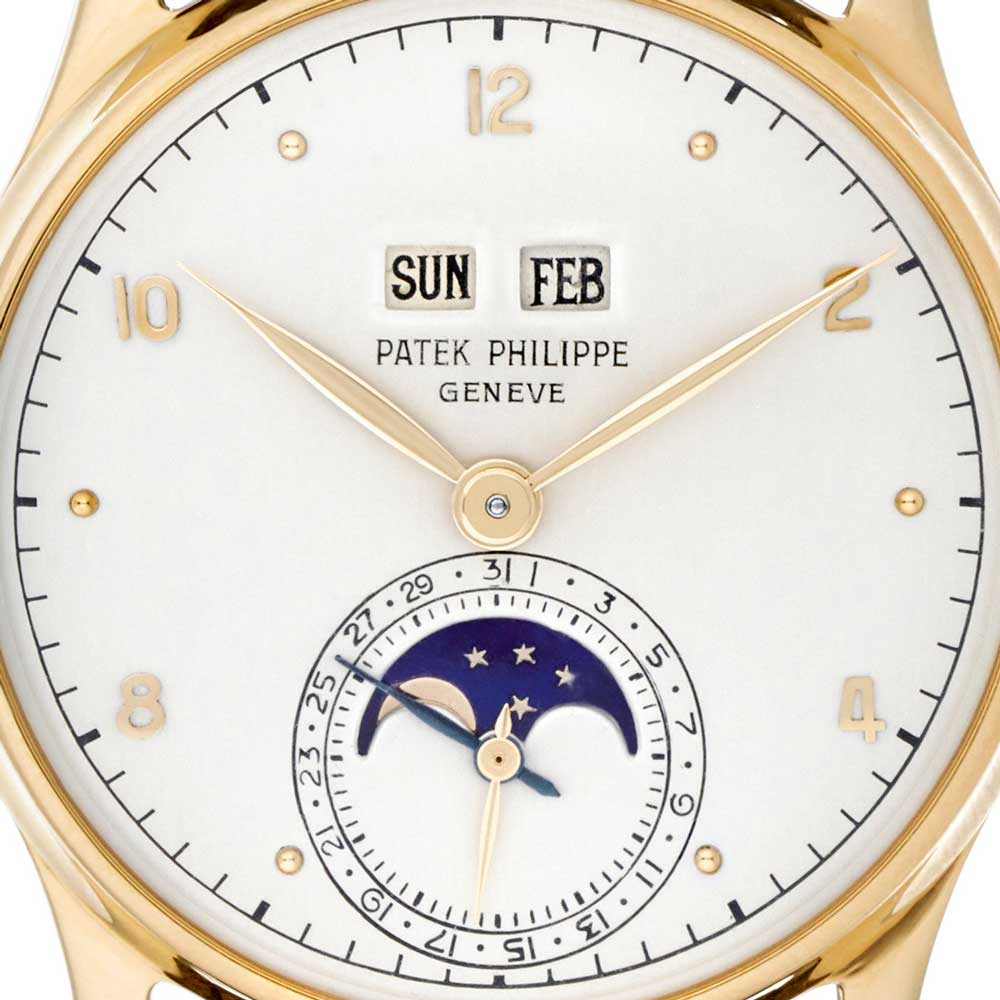

Patek Philippe ref. 1526

A unique Patek Philippe ref. 3448, with a leap year display instead of a moon phase shown on the subdial, circa 1975

Patek Philippe ref. 5208P

The Initial Forays

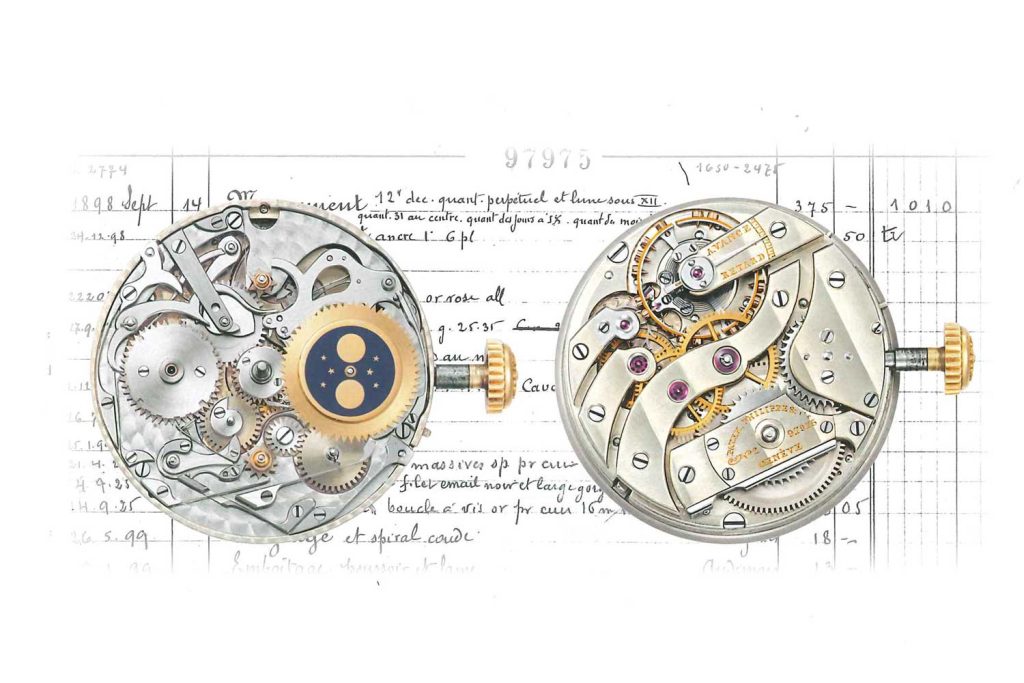

Patek’s very first perpetual calendar wristwatch dates back to 1925. But in reality, the movement for this watch goes even further back to 1898, when the maison made the movement to be housed in a women’s pendant watch. It is intriguing to imagine their thinking at the time. That this extraordinary complication capable of keeping time, date, day, month, year and even moon phase would appeal to a very specific female client. The watch went unsold and a quarter century later, this exceptional movement was re-cased in a beautiful yellow-gold wristwatch replete with hunter back and a large fluted crown. The 34.4mm-diameter case also featured stunning hand-engraved lugs, a tradition still associated with Patek to this day. The grand feu enamel dial of the watch was most likely turned 45 degrees from the original orientation of the movement — the pendant watch was probably intended to be worn crown up at 12 o’clock. As such, small seconds now appeared at nine o’clock and moon phase at three o’clock, while you could easily imagine them to be in the more traditional six and 12 o’clock positions. Date was told using a large centrally mounted hand off a red scale at the dial’s perimeter. The day-of-the-week subdial is located at 12 o’clock while the month subdial is at six o’clock. It is interesting to note that Patek would never repeat this design again. The watch designated number 97975 and which featured Patek’s 12-ligne movement was sold in 1927 to an American collector named Thomas Emery and today constitutes a historical treasure that is simply priceless.

Patek Philippe 97975: The First Wristwatch with Perpetual Calendar (Image © Revolution)

An illustration of the movement inside of the Patek Philippe 97975: The First Wristwatch with Perpetual Calendar (Image © Patek Philippe)

In 1937, a mere five years after the extraordinary Stern family took ownership of Patek Philippe, the firm once again re-entered the world of the perpetual calendar wristwatch, this time with an utterly unique and singularly animated timepiece designated the reference 96. This was the first Patek wristwatch to feature twin in-line apertures on the dial, on either side of the cannon pinion, for day and month. Date is told off an inverted arc that sweeps dramatically across the top half of the dial and is read from a retrograde hand. Meaning that at the stroke of midnight on the last day of each month, it jumps instantly back to the number “1” corresponding to the first new day of the next month. Phase of the moon is relegated to six o’clock. This watch featured Patek’s 11-ligne movement made from a Victorin Piguet ébauche. This stylised and dynamically formatted retrograde perpetual calendar would become a staple at Patek many years later with the reference 5050 watch launched in 1993.

Patek Philippe created another first with the ref. 96 by fitting a retrograde perpetual calendar within a wristwatch

The First Serially Produced Watches

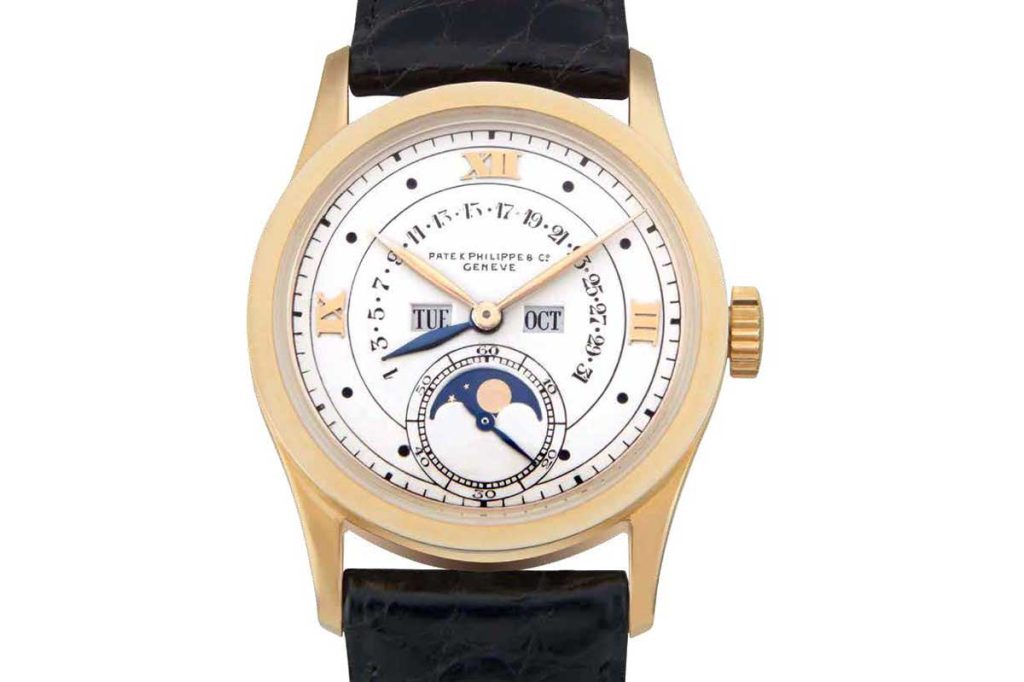

Ref. 1526

The first serially produced perpetual calendar. Launched in 1941 and made in 210 examples over 12 years

Ref. 1526

The 1526’s greatest contribution to the horological canon was the creation of the now-classic perpetual calendar format where the two apertures for day and month (first seen in the ref. 96) were elevated to take centre stage just below the 12 o’clock index. The cream enamel dial featured a highly legible combination of applied Arabic and dot indexes. Hands were large imperious dauphine-style units. This is the first instance in which date and moonphase indicator are combined into the subdial at six o’clock, which would forge the genetic underpinnings of the majority of perpetual calendar displays that would follow this watch. One of the reasons that the 1526 feels so clean is that the seconds hand has also been incorporated into the subdial at six o’clock, leaving a large expanse of beautiful clear dial.

Ref. 1526

Ref. 1526

Ref. 1527

Two watches made with 37.6mm cases, one featuring a chronograph and one without. Year of production, circa 1943

Ref. 1527 consists of two watches made with 37.6mm cases, one featuring a chronograph and one without, produced in 1943

Ref. 1527 non-chronograph version

Ref. 1591

Two watches made in 1944 with waterproof cases, luminous dials and hands. Forged the design underpinnings of the 2017 ref. 5320

Patek Philippe Ref. 1591 in Stainless Steel (Image © Revolution)

Refs. 2497 and 2438-1

Both are essentially the same watch, but the 2438-1 comes with a waterproof case and screw-down caseback. A total of 179 pieces made between 1951 and 1963

Ref. 2497

Ref. 2438-1

Because these are the first serially produced perpetual calendars with central seconds hands, both series feature a large visible seconds track around the perimeter of the dial. Because Patek had (temporarily) dispensed with the seconds hand at six o’clock, the indication for the date is now larger and significantly easier to read. For the first time, Patek also did away with the circular track framing the date, creating a much cleaner lower half of the dial. Because of the bigger size, better wearability and more contemporary feel of these watches, coupled with their greater rarity, the 2497 and 2438-1 watches sell for significant premiums over the 1526.

Ref. 2497

Ref. 2497 in rose gold, first series

Ref. 2497 in yellow gold, second series

Birth of the Self-Winding Perpetual Calendar

In terms of their capacity to provide you with calendar information, automatically compensate for the shifting 30/31-day rhythm of the months, and even knowing which years to add a day to February, perpetual calendars are technical marvels. If they were dogs, they would be border collies with preternatural cognitive abilities capable of playing Frédéric Chopin’s Nocturnes, while holding discourse on James Joyce’s stream of consciousness masterpiece Ulysses, all while herding a multitude of sheep. But they have one drawback, and that is when they run out of power because you forget to wind them or they’ve simply been set aside for too long, it can be mildly arduous to reset all of their indications. This was evidently not lost on Patek’s president Henri Stern for beginning in 1962, Patek became the first maison to create a self-winding perpetual calendar called the 3448.

Before plunging into the minutia of the most famous of Patek’s perpetual calendars, let’s stop to look at its precursor, the manual-wind 3449. This model is one of the rarest in Patek’s history with only three pieces crafted in 1961. These can be identified with the individual serial numbers 799000, 799001 and 799002.

Ref. 3449

This third watch also features a caseback engraved with the name of its owner, Geo. Poston, short for George Poston, a Texas real-estate developer who had purchased the timepiece for $5,550 from Linz Brothers, a jewellery firm in Dallas. In addition, his caseback is engraved with the French phrase “Qu’Hier Que Demain” or “More than yesterday, less than tomorrow”, which references a romantic poem by the French poet Rosemonde Gérard. Today this watch resides in the collection of none other than Mr Auro Montanari, otherwise known as John Goldberger. The movement is the 23-300Q, an ultra-thin manual-wind movement.

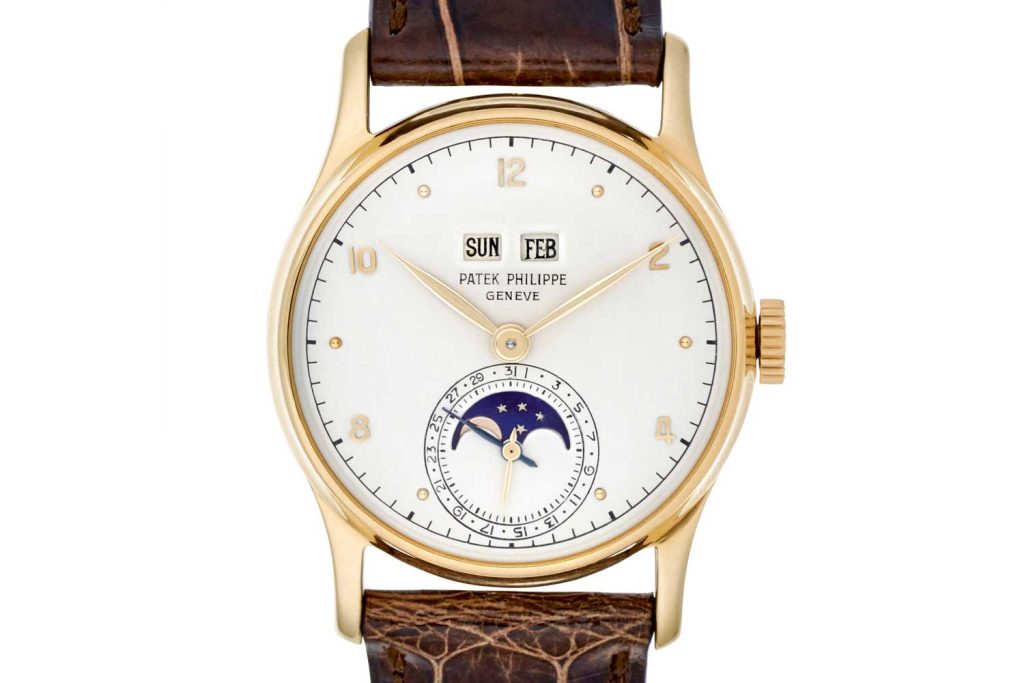

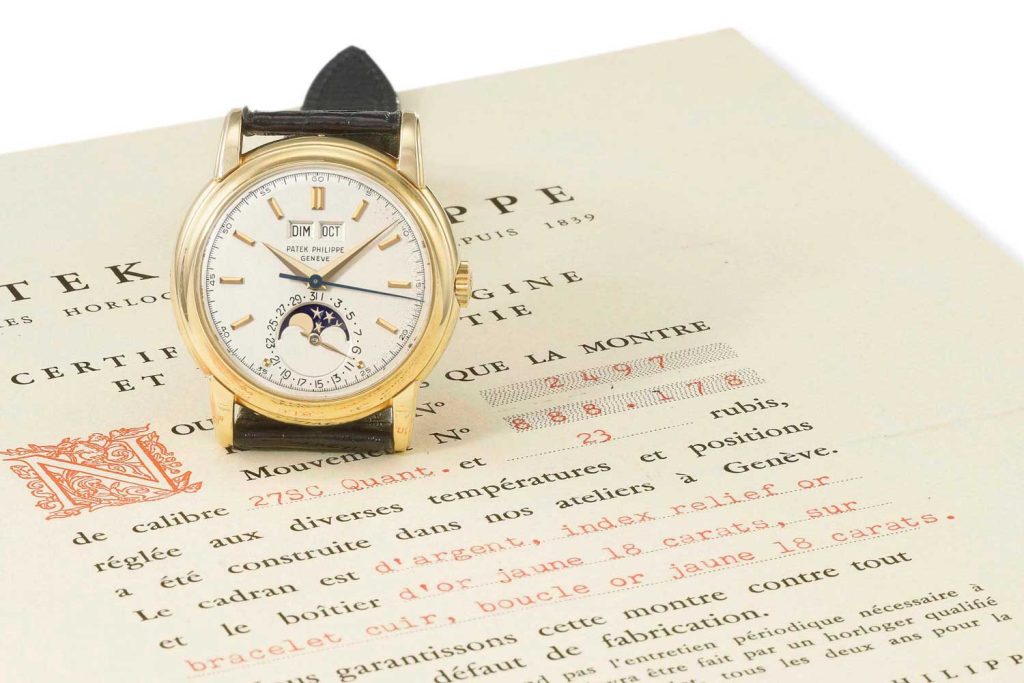

Ref. 3448

The first serially produced self-winding perpetual calendar wristwatch. Made from 1962 to 1981 with a total of 586 examples. The only one of its kind on the market for 16 years. The first watch with “Disco Volante” case designed by Antoine Gerlach. Also featured sharp futuristic lugs. Nicknamed “Padellone” for its 37.5mm diameter and relatively thin case. Two platinum watches made in 1997, long after the model was discontinued. Cases for the ’97 watches made by Jean-Pierre Hagmann

Ref. 3448

It is in interest to note that the watch’s Disco Volante design, which features a partially recessed crown, could have made it quite challenging to manual wind, which would offer an additional explanation as to why the 3449 was never put into serial production. In any case, the 3448 is the 20th century’s most iconic perpetual calendar. Close your eyes and imagine a watch with this complication and the 3448 will immediately appear. It is Zen reductive cool to the extreme! The markers are now thin, elegant baton-shaped units while the minute track is a stunning series of tiny applied dot markers (in the first three series). The hands are clean, bold sword-shaped units. But where did the seconds hand of the watch go? The same seconds hand which somewhat cluttered the subdial on the 1526, and which took imperious centre stage on the 2497, has been altogether dispensed with in the pursuit of the ultimate act of horological minimalism to render the purest expression of the perpetual calendar.

Ref. 3448

The 3448s can be further divided by their dials into four distinct series. The first three series all used grand feu enamel dials, short applied gold baton markers and sword-shaped hands. They all featured applied gold pearls for the minute track. Let’s pause for a moment to express just how difficult it is to execute these types of dials. First, these stunning white dials need to be rendered with perfect uniformity and be printed with their date wheels and Patek Philippe signatures in the space just below the twin apertures. Then these delicate dials need to be pierced to accommodate the applied markers as well as each individual pearl for the minute track. This piercing is clearly visible in the close-up images of the second-series white 3448 offered for sale by Christie’s in 2016.

Ref. 3448, first series dial

Ref. 3448, second series dial

Ref. 3448, third series dial

Ref. 3448, third series dial

Ref. 3448, fourth series dial

The second series made from 1965–73 has distinctly smaller and lighter printed numerals in the date ring. These numbers can appear either inverted or un-inverted, where they are not flipped from “11” to “23” and thus appear upside down. The Swiss hallmark can have the sigma symbol on each side (usually for post-1970 dials), referring to the use of gold indexes on the dial.

The third series made from 1971–78 is the same but now with distinctly larger numbers than the first and second series. It can have an inverted or un-inverted date ring and it will have a Swiss hallmark with the sigma symbols.

The fourth series made from 1978 to circa 1981. These are the easiest to identify because the dials are no longer grand feu enamel but modern brass dials that have been printed. Minute markers are no longer applied pearls but small printed hash marks. These watches also have the sigma symbols due to their gold markers. There have been some interesting one-off watches that have emerged in the lifespan of the 3448. One of these is a very intriguing white-gold 1974 ref. 3448 that appears to have been retrofitted later with a factory-original series-four luminous dial and luminous hands.

Of the four series, to my mind, the second series with its more restrained and subtle date ring is the most beautiful and integrates most perfectly with the 3448’s minimalist iconography. However, that’s splitting hairs as every one of these masterpieces is exquisite. All watches from the four series use the calibre 27-460 Q.

A Unique Piece and a Controversy

OK, so up until this point, all perpetual calendar watches while capable of adding the 29th to February on leap years had one shortcoming. And that was they had no display for where in the leap-year cycle you were, making adjusting your watch something of chore. Indeed, it would not be until the launch of the reference 3450 in 1981 that a regular production perpetual calendar watch would finally have a small aperture that would tell you where in the leap-year cycle you were. And it would only be in 1985, with the simultaneous launch of the 3940 perpetual calendar and the 3970 perpetual calendar chronograph, that you would have a full display for the cycle in a subdial.

Ref. 3450

Unique ref. 3448 with leap year in place of moon phase

There was, at one point, a controversial variant of the 3448 that emerged on the auction scene in the early 2000s. I use the word “controversial” as there was much doubt over their legitimacy — a story well chronicled by Cara Barrett of Hodinkee. And the general consensus was that these were prototype or experimental dials created by Stern Frères, but never intended to be fitted to production 3448 watches. One key detail supporting this is that in the watches that did emerge at auction, all of them still had the corrector for the moon phase even though the dial didn’t display it, which is totally out of character with Patek’s traditional sense of perfectionism.

Ref. 3450

Successor to the 3448, made from 1981–85 with a total of 244 examples. Featured leap-year indicator and was powered by the calibre 27-460 QB, an updated version of the base calibre that was launched in 1962

Ref. 3450

The ’80s to the ’90s — The Era of the Most Undervalued Vintage Perpetuaal Calendars

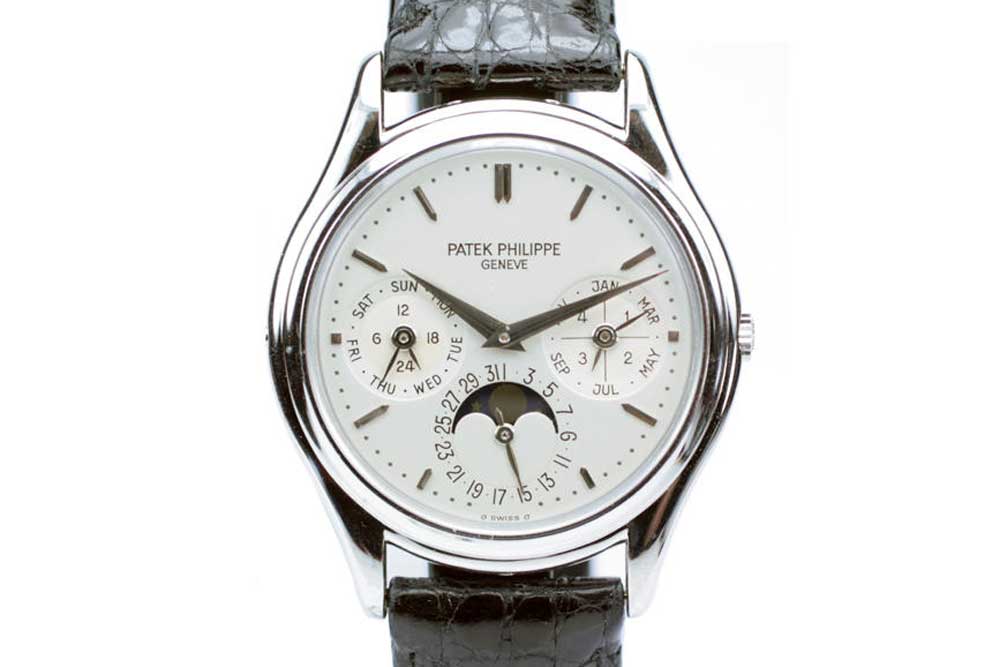

Ref. 3940

Launched in 1985 (post-Quartz Crisis) together with the ref. 3970. The first perpetual calendar watch with leap-year and 24-hour indicators in subdials. 36mm in diameter and powered by Patek’s micro-rotor calibre 240. Patek owner Philippe Stern’s daily watch

Ref. 3940

Both the 3970 and the 3940 are perpetual calendars using the same in-house-designed module which places a leap year indicator in the subdial at three o’clock, and a 24-hour time indicator at nine o’clock — important as the module should not be adjusted near the midnight threshold when the calendar information is changing over. While the 3970 united this module with the venerable Lemania 2310 chronograph calibre, the 3940 marries it with possibly the most beautiful micro-rotor equipped automatic movement ever designed, Patek’s extra-thin calibre 240.

Cal. 240

The 1990s and the Return of the Retrograde Perpetual Caledar

Ref. 5040

Launched in 1992. Patek’s first tonneau-shaped perpetual calendar, and also the first to use Breguet numerals

Ref. 5040

Ref. 5050

Made from 1993 to 2002. The first perpetual calendar with retrograde date based on the Patek pièce unique ref. 96 from 1937

Ref. 5050

Ref. 5050 in yellow gold case with black dial and applied Arabic numerals

Ref. 5041

Introduced in 1995, Patek’s second serially produced tonneau-shaped perpetual calendar. Made in no more than 30–50 examples

Ref. 5041

Ref. 5059

A more robust-style Patek perpetual calendar, featuring an officer’s caseback

Ref. 5059

So, here ends this historical journey of Patek Philippe with the perpetual calendar just before the turn of the new millennium.