Tudor

Tudor on Expedition

Hans Wilsdorf was a man who saw an opportunity to support expeditions to both test his watches and capitalise on the incredible marketing opportunities they offered. He was confident that not only could his timepieces handle the conditions, but that they would thrive and work flawlessly. I wrote extensively about the Explorer and the pre-Explorer watches, supplied by Rolex, that were used during the historic ascents of Everest. You can read the article here.

This time the focus is on the younger brother of the Wilsdorf family, the Tudor Oyster.

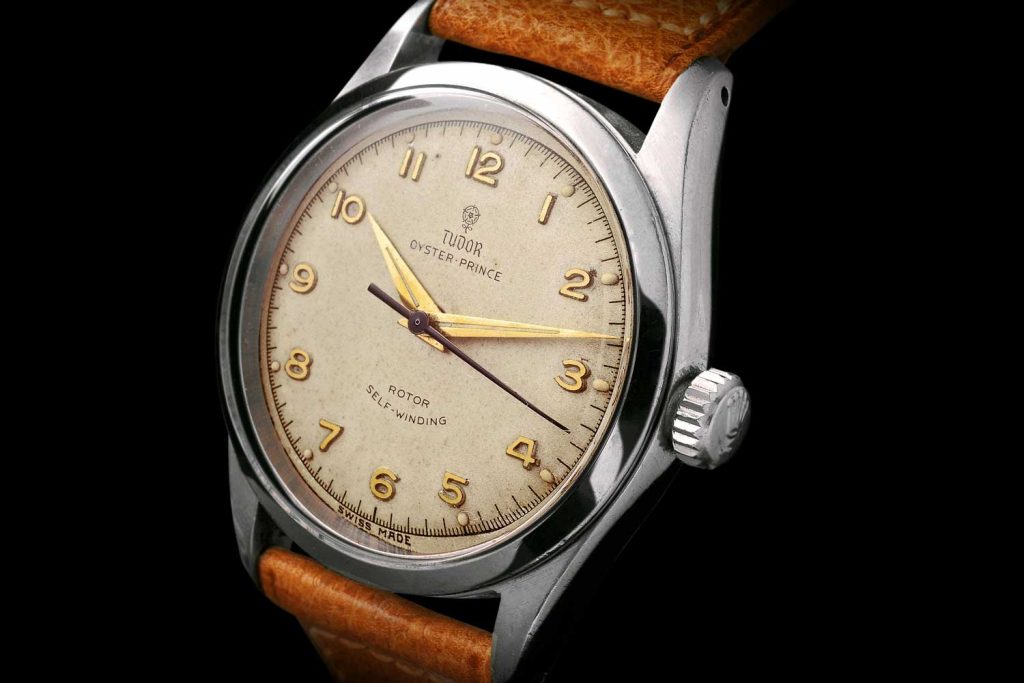

I have long been fascinated by the Tudor Oyster watches from the early-1950s, with the vast array of dial variations and case references. The first Tudor Oyster watches were sold in 1946 and housed manual-wind movements. The Oyster Prince was unveiled in 1952 – Prince signaling an automatic movement and the equivalent of the Rolex Perpetual. The early watches were of what collectors refer to as monoblock construction (or monoblocco in Italian) where the mid-case and bezel are made from one piece of steel. The Oyster case refers to the screw-down winding crown, screw-on caseback and pressure-fitted crystal – all of which combine to create a waterproof watch-case that is hermetically sealed like an oyster. Truly rugged in construction, these watches were conceived as pieces to be worn for all rugged occasions as highlighted in early Tudor Oyster adverts featuring construction workers, motorbike racers and polar explorers. And there was no more rugged test for the watches than an expedition to Greenland.

Tudor Oyster Prince ref. 7809 issued to Roy Homard and that now resides in the Tudor museum collection

Royal Ascent

The British North Greenland Expedition (BNGE) 1952-54, was led by Commander James Simpson and commissioned by Queen Elizabeth II and Winston Churchill to survey and research the ice cap. A total of 30 men took part in the expedition over the two years and were made up from representatives of the armed forces and various scientific fields including the areas of geology, meteorology, glaciology and physiology. As well as research work, it was also an opportunity to train the military servicemen in Arctic conditions. The expedition was almost entirely carried out by the British, but the Danish Army did provide a captain, an army surveyor, who was sadly the one fatality of the mission in 1953. Denmark claimed Greenland as their sovereign land in 1380, but officially the Kingdom of Denmark adopted the island in 1953 – right in the middle of the BNGE. There would have been a lot of political activity in Denmark at this time and so I expect that it was a diplomatic necessity to have a representative of Denmark on the BNGE.

The BNGE expedition team on arrival at basecamp

Brittania So with landed planes

The Tudor 7809s that were supplied had two different dial configurations in slightly smaller watches measuring 34mm. One dial version was very similar to the Rolex dial with simple baton hour markers and a double baton at 12 o’clock. The second dial variation resembled the Explorer watches that would come later from Rolex and the Ranger series from Tudor, with applied Arabic numerals at 12, 3, 6 and 9. We remain unsure how many of each dial was provided.

Surgeon Lieutenant Jock Potter Masterton’s 780 with 3-6-9 dial

Performance Under Pressure

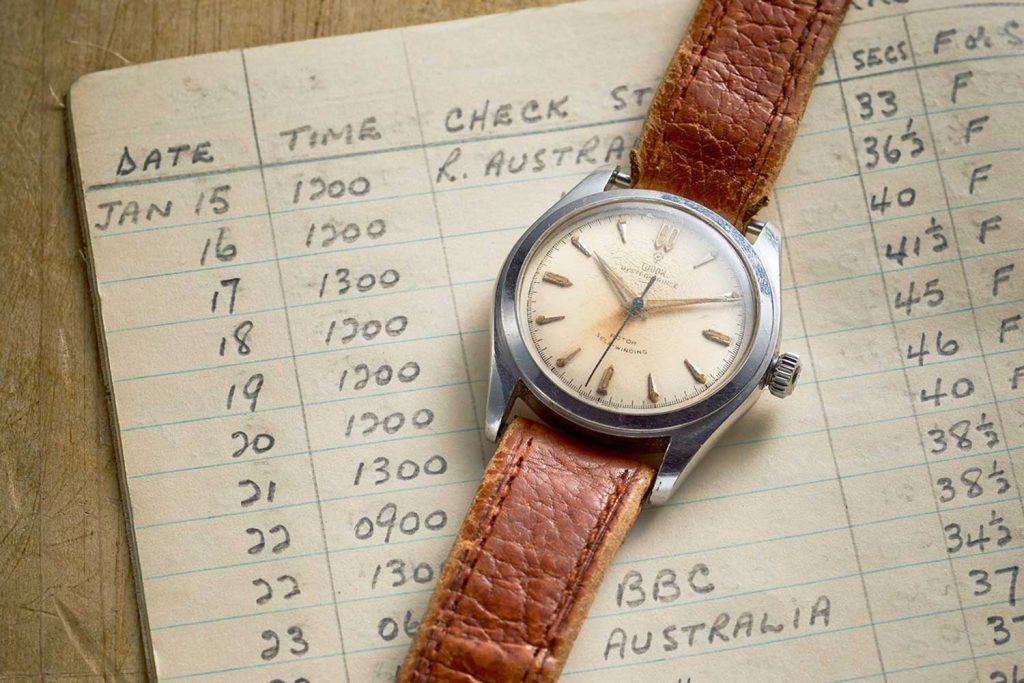

A key part of the agreement between the expedition and Rolex was the monitoring of timekeeping of the Tudors. The team would check their 7809’s timekeeping against BBC radio signals and note the accuracy. These notes then formed part of the Rolex research and development program and the company’s pursuit of excellence.

One member of the team, the Officer in Charge of Vehicles – Captain JD Walker of the Royal Engineers, was very happy with his Oyster Prince. In a letter to Rolex he stated that having spent 13 months in Greenland he had: “Extreme admiration for the Rolex Tudor Oyster Prince which I wore on my wrist throughout my tour with the Expedition.” The letter describes the extreme temperature changes from 70°F to -50°F (21°C to -46°C) and various tasks undertaken whilst wearing the watch including hut building, riding dog-sleds, driving the Weasels, and the watch inevitably being regularly immersed in water. He concludes: “Despite these trials, occasional time signals broadcast from England proved that my Rolex Tudor Prince watch was maintaining a remarkable accuracy. On no occasion did it require to be wound by hand.”

Roy Homard and members of the expedition

“Lake life”

Landing on the lake meant a boat was need to reach the shore

The Homard 7809 with timekeeping notebook

“Weasel Watch” – waiting for the next supply drop atop a Weasel

Getting that sinking feeling with a Weasel in distress

During the expedition, dog-pulled sleds were the easiest way to travel

The Lost Tudors

Another important discovery was that of the Tudor 7809 that was issued to Chief Petty Officer Herbert “Dixie” Dean, who was a senior radio operator on the expedition. The Herbert Dean watch had the dial version with applied Arabic numerals, complemented by stunning dagger hands and a vibrant blued-steel seconds hand. The watch was discovered by vintage watch collector Martyn West, who lives locally to the cousin of Herbert Dean.

I spoke to Martyn and he told me that Dean had left the watch to his cousin when he passed away. The cousin recalls being told that the watch was “issued to Dean as part of his military service when he was stationed in Greenland to support a scientific expedition”. As is often the case, she had forgotten about it. Much like the discovery of the Homard watch, Dean’s watch was rediscovered in a drawer. It wasn’t working and Martyn had it serviced and enjoyed wearing it for a while, before selling it to a collector in the Far East.

The third and perhaps most talked about of the known examples is the one that belonged to the Medical Officer, Surgeon Lieutenant Jock Potter Masterton.

Masterton’s caseback engravings

The markings on the 7809’s original winding crown